This summer my weekly cycled commute along the king’s processional route from Berlin to Potsdam became something of a ritual, and like all rituals, it became a mundanity — to the point that I no longer needed to pause to admire the wide expanse of the Wannsee; no longer felt the usual slight buzz of excitement of living history as I crossed the Glienicker Brücke and with it the furthest edge of what had been West Berlin; I no longer even clocked the garishly grandiose monstrosity that is the Palace Sanssouci as I pedalled through the crowds of tourists at the edge of the park on the final stretch to my university building.

Indeed, all that I regularly take notice of in Park Sanssouci are the sheep, who are recent immigrants. They are frequently moved around to a new spot, surprising me with their baleful expressions as I round a corner and find them in a field that was until recently empty. Their fence comes with them; I am told they serve as ecological lawnmowers, being ushered endlessly on, hectare by hectare, until they have chowed down on the lawns of the entire park — upon which, I assume, they begin again, probably unaware of the cyclical nature of their Sisyphean task. They stare listlessly at me as I speed past them, gloriously out of place in this most artificial and carefully delineated of public gardens, where the figureheads on the Chinese House stare down reproachfully at passers-by and their ovine neighbours, as if disapproving of modernity intruding on a bygone gilded age.

Yet Logan February’s beautifully evocative essay in the Berlin Review reminded me to notice the palace again. Among the personal reflections on the pain of colonialism, it taught me the theory that the phallic, errant and ungrammatical comma in the words on the facade — “Sans, Souci” — may have been a nod to Frederick the Great’s homosexuality and the status of the palace as a male-only haven for him and his courtiers. Les potsdamistes was a term apparently used throughout Europe to refer to homosexual courtiers. Unthinkably today, Frederick and his elite circle sought and found an emancipation and freedom in Potsdam that was not possible in staid, stuffy Berlin.*

When I next cycled by the palace I allowed my bike to come to a halt, a few inches in front of the sign that forbade cycling any further. (I had been subject to the Teutonic wrath of the park security officers on more than one occasion for crossing this line.) I have now been regularly travelling to the old Prussian capital for two years and have spent more time than I ever planned to in its broad boulevards and gorgeous nature. I am, on occasion, charmed by it. But by now, I have also slightly written off Potsdam — as the capital of a state where 29% of people vote for a far-right party; where friends who are people of colour tell me they no longer dare to dare to tread; where, despite being barely an hour’s hard pedalling away, Berlin is just a mirage winking on the horizon, more of a concept than a reality.

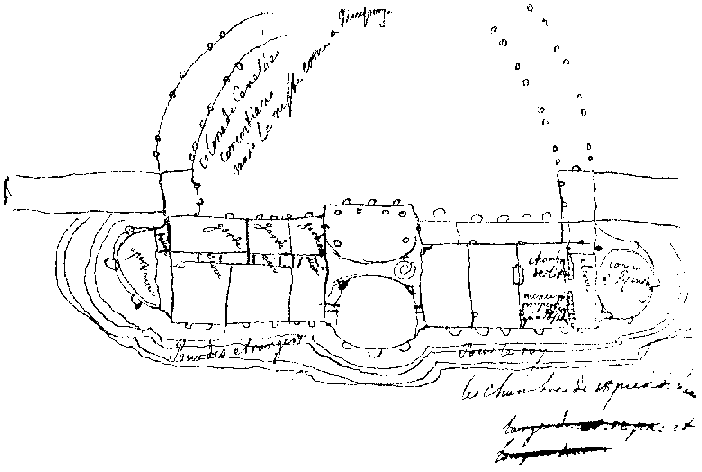

The palace itself is grotesque in its Rococo swirls and beauty. I am reliably informed by Wikipedia that Frederick drew the architectural designs himself, a delightfully unprofessional child’s depiction of what a palace should look like (see above), and refused any practical suggestions — for example, to allow the servant’s quarters and kitchens to be any closer to his rooms. He fired at least one architect. He threw wild parties and orgies here. The American, Dutch and Spanish tourists, wrapped up against the autumn cold, take photographs of these orgies. This is completely normal; they notice nothing.

Desire hangs heavily in the air at this place. I wonder if cruising goes on in Park Sanssouci. It seems improbable — the park is locked at night and has an army of gardeners and security guards on duty. But I am never unsurprised by the ubiquity of queer lust. Reality allows blurriness and complications. The clear lines of the palace grounds; the sign not to cycle any further; the 29% of the populace who are AfD supporters — none of these clear demarcations reflect the complexities of reality in any meaningful way.

But whatever goes on in this grandest of Potsdam’s parks today, I remain no potsdamiste. I am not even a Berliner, not properly. The mirthless sheep, chewing solemnly on their cud, are far more real than the ephemeral presence of the gay emperor or the dichotomy of Potsdam and Berlin or even a sense of personal emancipation. Once, a lifetime away from Sanssouci, a farmer friend handed me a newly-born lamb to hold on a crisp December night and I felt its heartbeat through my entire body. That was real. I cycle on.

*Although Berlin is far from a paradise, queer or otherwise, and I worry on reflection that this piece is needlessly binary. But some artistic oversimplification may be forgiven to make a point.